Widely regarded as ‘the first significant modern Muslim artist from South Asia,’ Chughtai received numerous accolades throughout his career, including the title of Khan Bahadur in 1934, Pakistan’s Hilal-i-Imtiaz in 1960, and the Presidential Medal for the Pride of Performance in 1968. His influence extended beyond South Asia, earning admiration from figures like Allama Iqbal, Pablo Picasso, and Queen Elizabeth II.

Born in Lahore in 1897, Chughtai grew up in the historic neighbourhood of Mohalla Chabuk Sawaran. He came from a lineage of artisans, inheriting a deep appreciation for craftsmanship, architecture, and decorative arts. His artistic journey began under the tutelage of his uncle, Baba Miran Shah Naqqash, who taught him naqqashi (decorative art) at a local mosque. This early exposure to intricate ornamentation and traditional design would later shape his distinct aesthetic.

In 1911, after completing his education at Lahore’s Railway Technical School, he pursued formal training at the Mayo School of Art. Under the guidance of Samarendranath Gupta, a disciple of Abanindranath Tagore, he was introduced to the Bengal School of Art—a revivalist movement that sought to establish an indigenous artistic identity distinct from Western academic painting. Although he initially embraced this style, Chughtai’s later work departed from its soft, wash-based technique, favouring stronger outlines, bolder contrasts, and intricate detailing, which became hallmarks of his own artistic vocabulary.

Chughtai’s artistic breakthrough came in 1916 when his first painting, created in a revivalist oriental style, was published in Modern Review. By 1920, he held his first solo exhibition at the Punjab Fine Art Society, marking the beginning of his rise to prominence. Throughout the 1920s, he gained international recognition through exhibitions with the Indian School of Oriental Art, solidifying his place as a pivotal figure in Lahore’s burgeoning modern art movement.

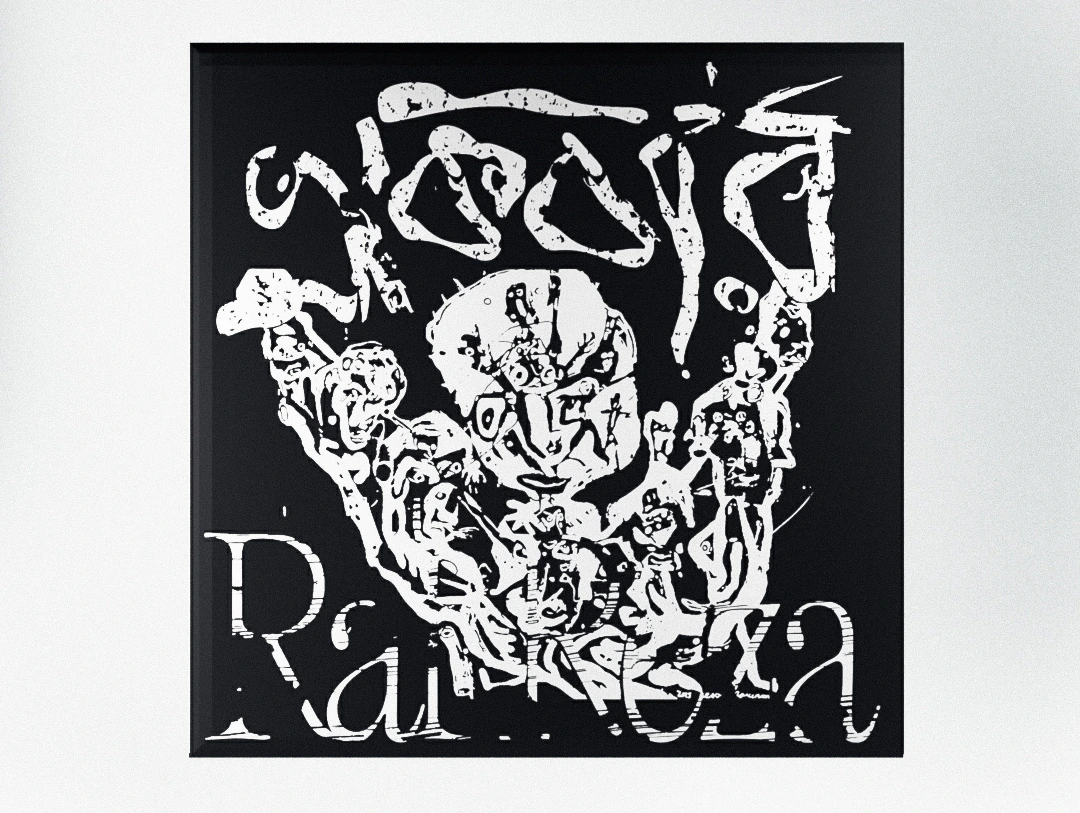

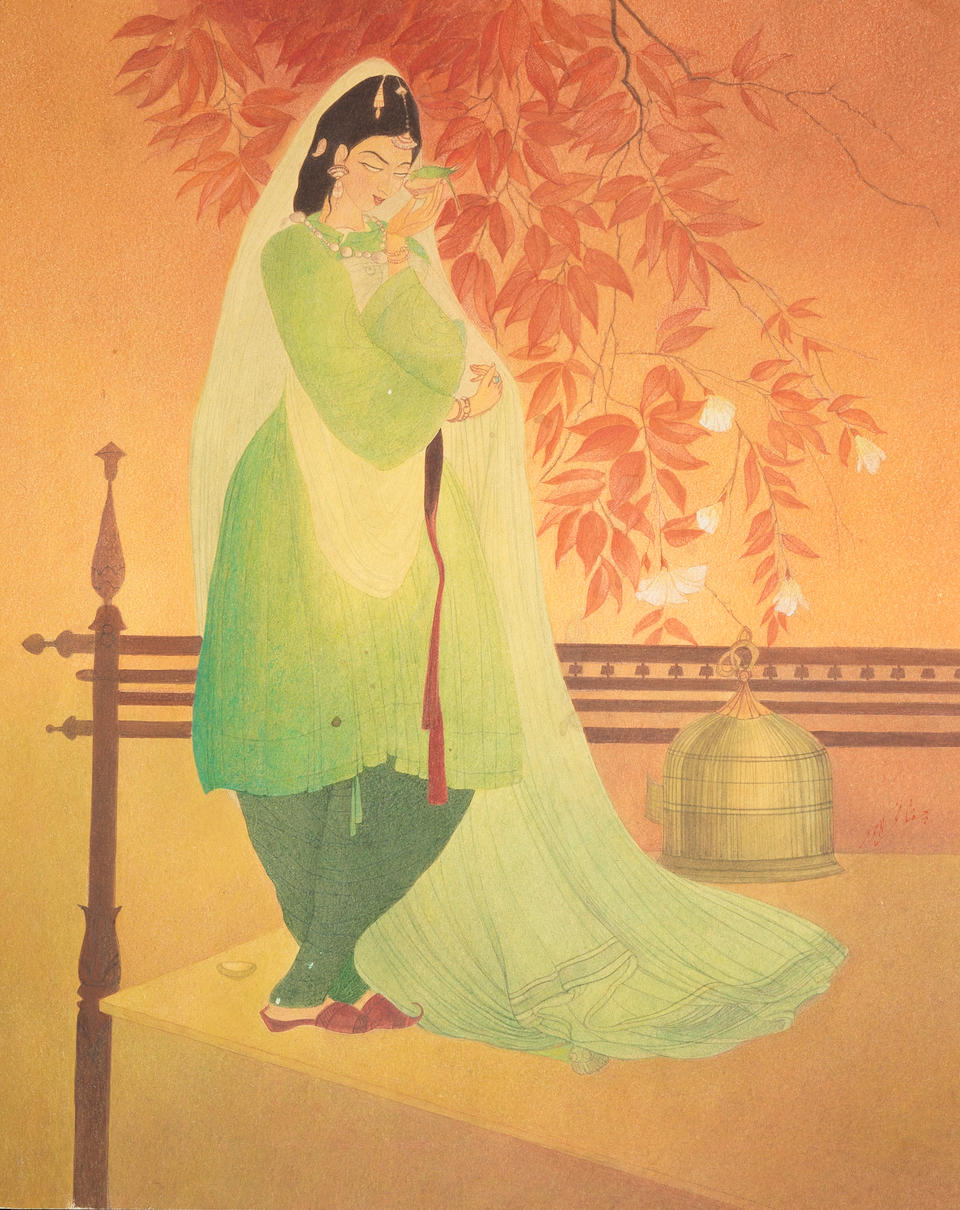

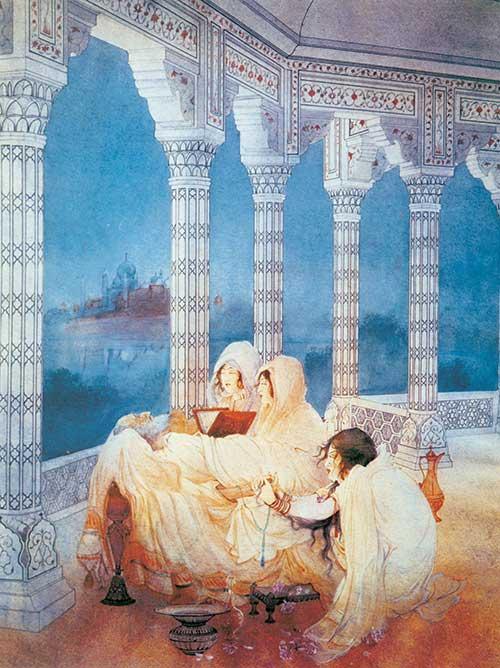

What set Chughtai apart from his predecessors and peers was not just his subject matter—often drawn from Mughal history, Persian legends, and Islamic calligraphy—but his distinctive treatment of form and composition. Unlike the soft, atmospheric washes of the Bengal School, his figures were defined by strong, elegant lines, an interplay of flowing drapery, and an almost ethereal quality. He masterfully balanced negative space, often leaving expanses of paper untouched to emphasize the delicate grace of his figures. His use of colours—vivid blues, deep crimsons, and gold highlights—evoked the richness of Persian and Mughal manuscripts while carrying a modern, stylized sensibility.

Although watercolour remained his preferred medium, Chughtai was a versatile artist. He expanded his practice to include etchings, an art form he refined during visits to London in the 1930s. Printmaking allowed him to explore new ways of rendering depth and texture, further enriching his artistic language.

Over a career spanning six decades, Chughtai produced an extraordinary body of work—around 2,000 watercolours, thousands of pencil sketches, and nearly 300 etchings and aquatints. Beyond visual art, he wrote short stories and essays, and designed stamps, coins, insignias, and book covers. His published works include Muraqqa-i-Chughtai (1928), Naqsh-i-Chughtai (circa 1935), and Chughtai’s Paintings (1940). Among these, Muraqqa-i-Chughtai, an illustrated edition of Mirza Ghalib’s poetry with a foreword by Sir Muhammad Iqbal, remains a landmark in book design.

Following Pakistan’s establishment in 1947, Chughtai emerged as one of the country’s most celebrated cultural figures, earning the title of Pakistan’s National Artist. His works were frequently gifted to visiting dignitaries, reinforcing his status as a cultural ambassador.

Salima Hashmi, an artist and curator, highlights Chughtai’s pivotal role in shaping modern South Asian art:

"He was a key figure in the early 20th-century movement to create an artistic identity rooted in the subcontinent. Chughtai rejected the dominance of the British colonial aesthetic, paving the way for a more indigenous expression."

His legacy continues to influence contemporary South Asian artists. While his signature style remains inimitable, many artists today draw from his fusion of tradition and modernity, particularly in their approach to calligraphic abstraction and narrative figuration. His emphasis on cultural identity has inspired generations of Pakistani painters seeking to balance heritage with innovation. His works are displayed in prestigious institutions such as the National Gallery of Modern Art (Delhi), the Victoria and Albert Museum, the British Museum, and the United Nations Headquarters. The Chughtai Museum Trust in Lahore remains a vital repository of his work, preserving his artistic contributions for future generations.

Chughtai’s graceful compositions, intricate detailing, and bold reimagining of traditional themes cement his place as a pioneer of modern South Asian art. His paintings do not merely depict history—they breathe life into it, offering a vision where past and present coexist in a world of elegance, beauty, and cultural pride.