A simple search about the crafts found in Udaipur led us to Koftgiri, but we were soon met with dead ends on any more information about the craft, its history, or its clusters in the present day. However, the premise of ornamental weapons, the grandeur of its history, and its intricate motifs, all set in the backdrop of the beautiful city of lakes, was enough for us to pursue contacts until we reached Mr. Parihar.

And so we set off, on a sunny afternoon, armed with cameras and notebooks, through the colourful, bustling streets of Udaipur to our unit. Turning around the corner of a busy lane into a nondescript alley, we reached a large archway, the entrance to the quiet Koftgiri unit. Mr Parihar (or Narottam ji, as we referred to him) introduced us to the space, which was his workshop and home. As we spoke to Narottam ji, we could see the craftsmen working away at products through a dark door to what we learned was the workshop area. As he took us inside to observe the process, we spoke more about the craft.

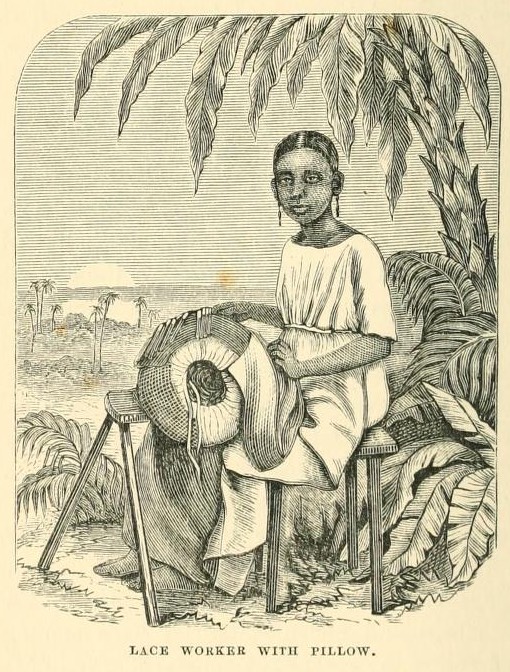

Koftgiri is the delicate art of gold and silver inlay on swords and dagger hilts, sheaths, shields, and other weaponry. Originating in Damascus, Syria, it was brought to India by Persian craftsmen and flourished during the Mughal Era. Initially practiced in the Mewar region of Rajasthan, the craft spread to other parts of the state. Koftgiri found patronage among the kings of Rajasthan, where it was adopted by Sikligars (traditional weapon makers) and inevitably became a part of the state’s culture. Today, it is found most notably in Jaipur and Udaipur. While similarities may be drawn to Bidriware, also a craft involving the inlay of gold and silver on metal products, Koftgiri is unique in its techniques, products, and symbolism. The craft elevated weapons to a status symbol, the designs often symbolising cultural narratives and representing the artistic inclinations of the yore. This legacy of designs has been carried forward through generations within craft families and have become as much of an heirloom as the weapons that sport them.

Similar to most other craft communities, Koftgiri had been a trade in Narottam ji’s family for centuries. He learnt the craft from his father, who, in turn, had learnt from his father. “Yeh talwar 300 saal se humaare parivar mein hai, pura sone ka bana hua,” I could sense the pride he held in his craft and his history entwined with it as he let me wield the 300-year-old sword with pure gold Koftgiri work at its hilt crafted by his forefathers and passed down through generations. “This sort of intricate work would never be possible today. In the past, the pace of life was slow, so our forefathers could take their time with it. Today, we have targets and deadlines to meet,” he said with a touch of frustration.

As he introduced us to his team of craftsmen, Kamlesh bhaiyya, Jitu bhaiyya, Sardar, and Manoj, we learnt their roles and, through them, the process of the craft.

With the example of the dagger they were crafting at the time, the work begins with the forging of the blade of this dagger, which happens in a separate unit. The blade is forged from a combination of mild steel and hard steel. The bars are placed together, heated, and beaten to flatten them. This process is repeated over and over until the hard steel and mild steel are combined into a singular block of steel. This is then cut and shaped into the form of the blade required and washed with acid. The acid dissolves the mild steel in the blade, forming patterns of grooves on its surface. They then move on to the hilt, which is made from Faulad, sheets of iron of 16-20 gauge, that they source from Hathipole, a market within Udaipur. These sheets are then cut and formed into the desired shape for the hilt. Once the hilt is formed, they cut out parts of it according to the designs they want to create. They then heat the piece with a Shaitaab, a blow torch, which turns the workpiece blue (for better visibility of the work). This is when Kamlesh bhaiyya takes over the workpiece to begin scoring fine cross hatches across its entire surface with a Chhaini, a specialised blade for the very purpose.

The purpose of these grooves is to hold the inlay that is to happen. Once this is done, Jitu bhaiyya or Sardar take over the inlay work, deftly placing the wires within the grooves with amazing precision. The inlay is reinforced into the grooves with a Salai, a blunt pen-like tool. The motifs are usually inspired by flora and fauna, gods and goddesses, and scenes of royal processions and hunting excursions. One can also note the geometric patterns in the motifs, inspired by Mughal art and architecture. The craftsmen also use small silver foils to form standard shapes like Bindis. Once the designs are finished, the product is then heated and polished with an Aqeeq (quartz) stone. This ensures that the soft metal inlay work is secured on the surface of the hilt. The last order in the process is to polish the dagger with a coat of machine oil or mustard oil to prevent the iron from rusting. Since our craftspeople didn’t have an elaborate packaging process or the budget for one, the product is then wrapped in bubble wrap for protection, placed in a cardboard box, and sent away for shipping.

Through the centuries, as weaponry has taken on a more ceremonial and ornamental role, the demand for Koftgiri products has declined, and the craft is slowly dying out. The clusters of craftspeople have also dwindled drastically. Narottam ji reminisced about the days he trained under his father and uncle, and spoke to us about his concerns for the sustainability of the craft. “A few of us used to observe my father working, and he taught us the skills. My elder brother, however, was not interested, and he now works in construction.” The younger generation within the craftspeople’s families want to take up other avenues of income as the craft itself is not financially lucrative.” I would like my children to also take up the craft. There are very few people who practice Koftgiri today…”, he trails off into a pensive silence. The craftspeople are making tremendous efforts to ensure that this delicate craft remains relevant to contemporary times and markets, which is why we now see jewellery like bangles made with the craft.

Recently, Koftgiri has received a Geographical Indicator tag, a certification from the government that provides legal guardianship against imitation, ensuring that the products sold have genuine origins. This has helped to protect, rehabilitate, and promote the craft, thus encouraging younger generations to take up the craft. At the time of my visit to the craft cluster, there was next to no support from the government for its rehabilitation. “My father made his livelihood out of this work, doing it by himself. There was no one else to support him with it. I wanted to save the craft, so I learnt it early on,” recalled Narottam ji.

Koftgiri is a significant part of the rich tapestry of arts and crafts in India. The tranquility of the small cluster, the intricacy of Koftgiri houses a legacy of a thousand battles fought and the pride of embellishing them. As a young researcher, designer, and learner, I went to the cluster to observe the craft, and I came back with moving personal histories closely tied to it. My tryst with Koftgiri led me on a voyage of discovery and a deep love for crafts.