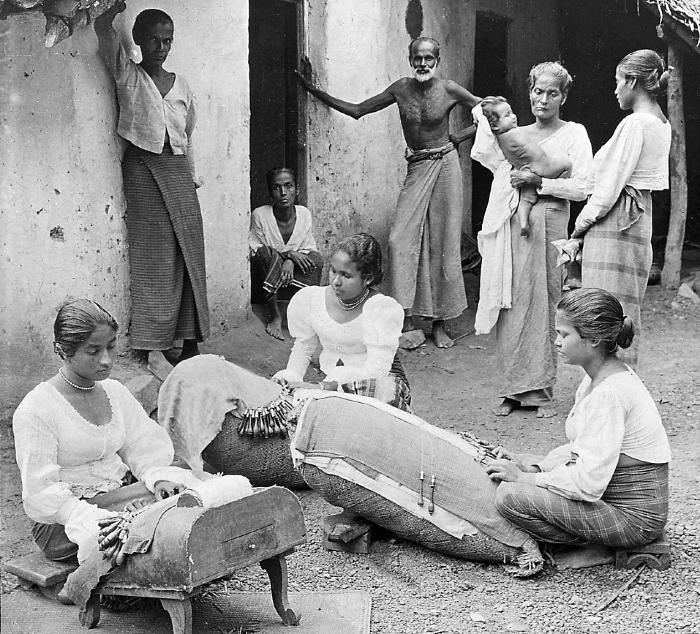

Lace in Sri Lanka has a quiet presence, with a history spanning over 600 years. Understated in effect, yet timelessly elegant, Beeralu rendu or bobbin lace from Sri Lanka embodies a certain resilience, representing a unique localisation of a foreign technique (img.1).

There is much speculation about the origins of the craft. The term Beeralu Rendu is directly taken from the Portuguese words bilro (bobbin) and rendu (lace). It is widely believed that the wives of Portuguese officers stationed in southern Sri Lanka in the 16th century taught the locals how to make lace. With the arrival of the Dutch, the industry further flourished and continued to be in demand under the British until the 20th century, when it started declining. Interestingly, some people believe that the technique was brought to Sri Lanka by Indonesian Malays, pre-dating the Portuguese, as they also used the term rendu for lace. The origins, therefore, remain contested.

The widespread adoption of the technique during Sri Lanka’s long colonial rule could be attributed to several factors such as religious conversions and associated behaviour changes such as increased participation of women in society, leading to more economic opportunities for them and their aspirations being expressed through clothing. The lace created was predominantly white in colour, demonstrating socially acceptable ideals of virtue and purity—signalling that despite greater mobility, women were still expected to be submissive and ‘pure’. When lace was introduced in Sri Lanka, it was made by women for women to wear, although in the West around the same time, it was being worn by men as well to signal wealth and social standing. It eventually went out of fashion for men to wear lace and became solely associated with femininity—a preconception still very much in existence.

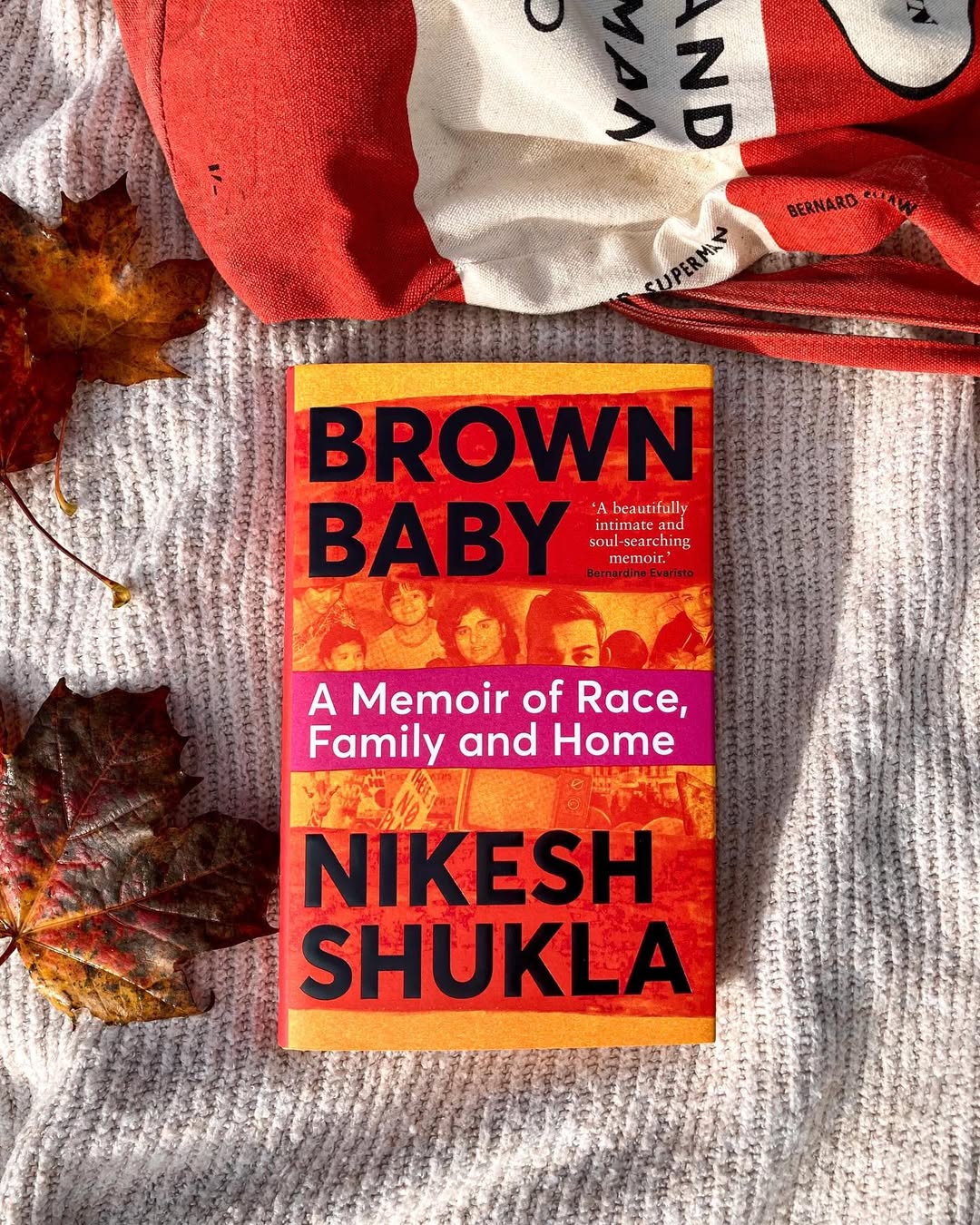

In earlier times, this white lace would be used to embellish clothing belonging to upper caste and aristocratic women and was a social differentiator. Kaba kuruthuwa (img.3), or a blouse with lace trims, was especially popular around in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

While other kinds of lacemaking do exist in Sri Lanka such as tatting, crochet and needlepoint; these techniques were introduced in the late 20th–early 21st century and lack the rich historical significance of bobbin lace.

Predominantly practised in the Southern coastal belt ranging from Kalatura to Dikwella, Sri Lankan women inherited Bobbin Lacemaking, or Beeralu Rendu from older women in their families. Oral knowledge transfer, and tacit knowledge, although perfectly legitimate means of learning, have led to a serious lack of formal documentation of this incredible craft. Despite the alarming lack of information, the craft in Sri Lanka is still prominent. Today, major centres for Beeralu are present in Megalle, Matara, Mirissa, Hambantota and Weligama. Women, typically over the age of 50, gather under the tropical sun, and make lace (img.4).

The paraphernalia needed to produce Beeralu lace includes a rotating bobbin pillow (kotta bolay or Beeralu kotte). This is fitted inside an elevated, large cushion made of coir and covered with cloth (img.6). A graph known as Koiru or ispisalaya with the design on it is pinned to the pillow, from which pairs of bobbins are suspended with yarn. Then, several strands of such yarn are interlaced and knotted to create intricate patterns. Commonly seen motifs in Beeralu lace are Sunflower, Jasmine, Bakini Flower, and Grape Vine. Some of these exact patterns, such as the Jasmine, are also seen in Portuguese lace (img.5). 100% cotton yarn is preferred for the lace, and until very recently, the only colour used was white. Nowadays, black and other colours are making an appearance to attract a wider range of consumers.

Small businesses producing Beeralu lace in southern Sri Lanka were common, before the tsunami in 2004 led to widespread destruction and grave losses—a great blow to an already unstable industry. Fortunately, the disaster led to renewed rigour with concentrated efforts to revive the previously languishing craft, many of which were supported by initiatives by the National Handicrafts Council in Sri Lanka, such as the Sipnara Handicrafts Centre.

Today, there is hope, with younger generations taking an interest in their histories and reclaiming bygone traditions. There is support through tourism (img.7), which has been actively promoted in recent years, leading to a significantly improved market potential for Beeralu lace products. Lace trims are applied to a range of products like cushions, sarees, dresses, shirts, table clothes and even made into jewellery like earrings and necklaces. Brands such as Kur by Kasuni Rathnasuriya, whom we spoke to for this article, have been incorporating the craft into their products since 2012. Despite being from Galle and growing up around the craft, she did not take an interest in it until she went to design school. Today, her brand has brought handmade Beeralu lace from Galle to a niche audience in New York and Sri Lanka through its unusual placement in garments, breaking away from its stereotypical associations (img.8).