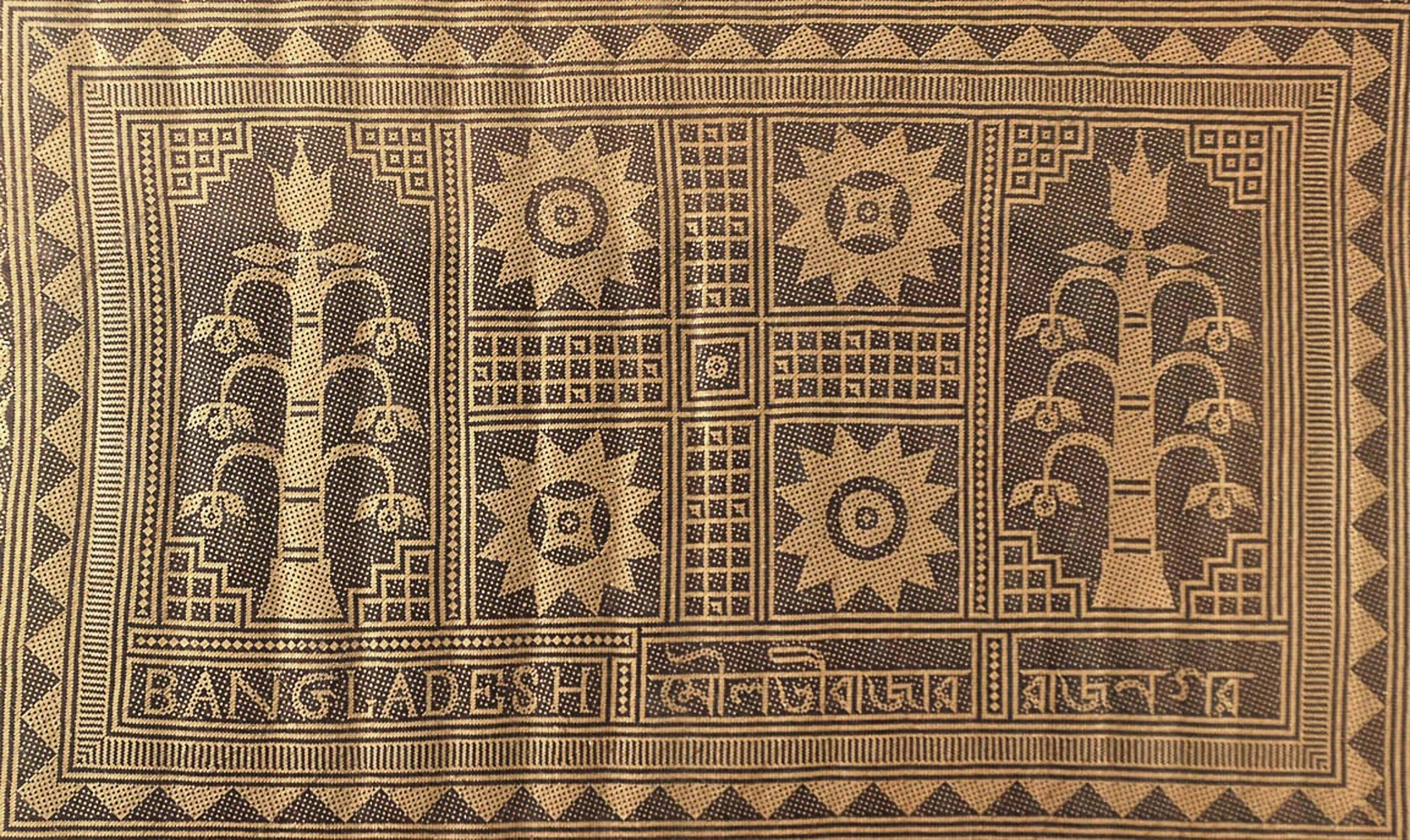

My friend’s summer throne, Shitol Pati, is an intricately woven mat made from green cane. The name literally translates to “cool mat”, which is quite a straightforward presentation of its purpose- to offer cool comfort in the tropical climate of Bangladesh. The craft drew the world’s attention to Sylheti craftsmanship. From Emperor Aurangzeb to Queen Victoria to Rabindranath Tagore, Shital Pati found appreciation among influential patrons through centuries.

Remembering my grandfather’s compulsory siestas on a pattamadai pai, a similar woven mat, in humid Chennai weather, I enthusiastically related to my colleague’s anecdotes about summer nights spent on the Shitol Pati. Even with the similarities in our cultures, I couldn’t ignore the fact that Shitol Pati was far more intricately designed than any pai I had sat on.

The mats are made with Murta, a type of green cane that is found predominantly in the swampy forests of Sylhet. The region is blessed with not only the raw material but also craftspeople (known as patikars) and craft families that have carried the tradition of this craft over generations.

Once the murta is collected, its stems are cut, soaked in water, and tied into bundles. The bundled wicks are then boiled in rice starch and different leaves like amra, jarul, tamarind, and cowpea. This is done to make them shiny and durable. The bundles are also boiled in natural or synthetic dyes for the vibrant designs that are so loved.

“The patis we have at home are bright colours”, he said, offering me a segue into my passionate arguments about the western chromophobia and the colonial supremacist notions of refinement (a dialogue for later).

Once prepared and dyed, the patikars skillfully weave these strips into intricate patterns using a traditional handloom. The motifs on Shitol Pati are often geometric patterns or representations of the lush region and rural life.

The variety of Shitol Patis are based on the smoothness of the wick, weave and design. Sikis are the smoothest variety and they take about four to six months to be woven. The Adhuli variety are less smooth than the Sikis but are usually more in demand and take about three to four months to finish. The Lalgalicha, Dhadhuli and Mihi are known to be a decorative variety.

“Late in the evenings, my cousins and I used to take a pati upstairs to sit on the terrace”, my colleague recounted, and I mean, rolling out a pati is such an invitation to convene, isn’t it?

The product and the craft itself is community oriented. It is a family-based craft, being passed down generations through informal apprenticeships of the younger members of the family. The women of the family play a significant role in the craft. Young girls often take on years of apprenticeship in weaving, mastering it over time. In providing the women a way to financially contribute towards their families, the craft stands tall as a symbol of empowerment.

As the weaving takes place in the courtyard or shared spaces in the community, neighbours often drop in to watch and appreciate the weavers. Shitol Pati brings the community together.

One distinctive trip to my grandparents’ house in Chennai, my great aunt unfurled a light, crinkly mat for her afternoon coffee sit down. “Oh we got a new plastic pai. We have so many guests visiting and staying over, it’s just a cheaper option”, my grandmother said. It was really the sound it made while being laid down that felt like an imposter.

In recent times, plastic alternatives have been replacing Shitol Pati in the markets as they are faster and cheaper to produce. Moreover, people’s lifestyles have undergone a change, with other accessible products replacing the mats in their purpose. The demand for the patis has drastically dropped. The patikars have been trying to mitigate this by expanding their product portfolios to home decor, bags and more.

The Shitol Pati business is seasonal since the mats serve a cooling purpose. So the off season of the business is a struggle in itself. More and more patikars are finding alternate avenues of employment as the craft becomes unsustainable as a livelihood. This has drastically reduced the number of practising patikars in an already limited number of craft families.

Murta, the key raw material for Shitol Pati, is also slowly disappearing due to population growth and subsequent development activities. The sustainability of the craft is in question.

Shitol Pati fairs across Sylhet during summer and monsoons already exist to sell and spread awareness about the craft. “The fairs are popular in the Sylhet region. Every year, around twenty Shitol Pati fairs are arranged in different areas of Sylhet. Depending on the quality and size a Shitol Pati costs one thousand taka to twenty thousand taka”, said Jahirul Islam, a Shitol Pati weaver in an article with Daily Sun.

In 2017, UNESCO declared Shitol Pati to be an “Intangible Cultural Heritage” of Bangladesh. Gitesh Chandra Das and Harendra Kumar Das presented the craft at UNESCO’s 12th International Conference.

The government’s efforts towards preserving the craft have come in the way of these fairs and organising these craft families into cooperatives. This ensures safeguarding of the craft, imparting of its skill and a guarantee of its profitability.

The Ministry of Land has granted the Shitol Pati community access to government owned land without taxes or rent to grow Murta. They are also reviewing the proposal for long term allotment of government land to the Shitol Pati community. The government’s scheme to connect rural growth centres has been implemented by bringing the Shitol Pati producing regions into the extensive road network.

While the collaborative efforts of patikars and the government continue to spread awareness of the craft, we as individuals can shop locally and shop for the environment.

“These days we are all sitting by ourselves, texting each other from one room to another. That culture of sitting together and having conversations is gone now”, said my colleague, scrolling on his phone.

The active efforts by the government and the craft families in rehabilitating Shitol Pati provide hope for its resurgence. The craft brings people together, both in making and in usage. I dream of a day when we embody this ethos, sitting on our patis with our favourite people, and slowing down.

%201.png)