Part I. Colonial Legacies in Botanical Gardens

Traditionally, botanical gardens are curated and organized like museums, displaying living foreign objects (Nielsen, 2023). However, this approach can create an alienating atmosphere that symbolically distances foreign species from the local environment, and perhaps even extends to cultures. The success of botanical gardens primarily comes from extensive travels of colonizers, where everything outside the cultural norm of colonizer entities was considered “exotic” and emphasized as “strange” and “dangerous” (Baber, 2016). What may seem like a purely ecological issue, foreign plant species, is tied to colonial histories, as many of these plants outcompeted native species and are now termed “invasive” (Schneckenburger, 2010). Furthermore, there is little respect and care for these species, and they are instead sentenced to complete chemical eradication.

Narratives are not just stories; they are tools of power. During colonial rule, European empires used narrative as a strategy to justify domination, casting colonized lands as “uncivilized” and in need of control. This framing was not abstract; it materialized through institutions like botanical gardens (Baber, 2016).

These gardens did more than collect and categorize plants, they curated a worldview. They turned colonized flora into spectacles, reinforcing hierarchies of knowledge and ownership (Nielsen, 2023). But the logic of display extended far beyond the plant world.

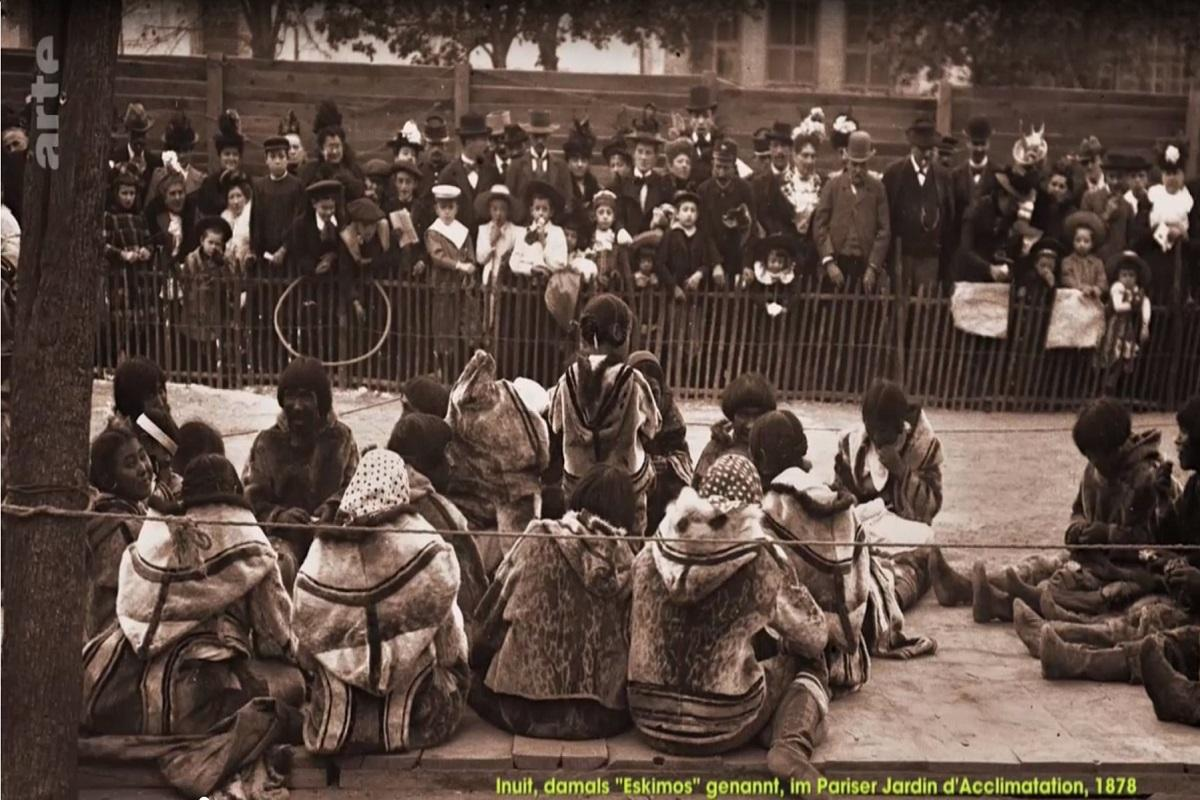

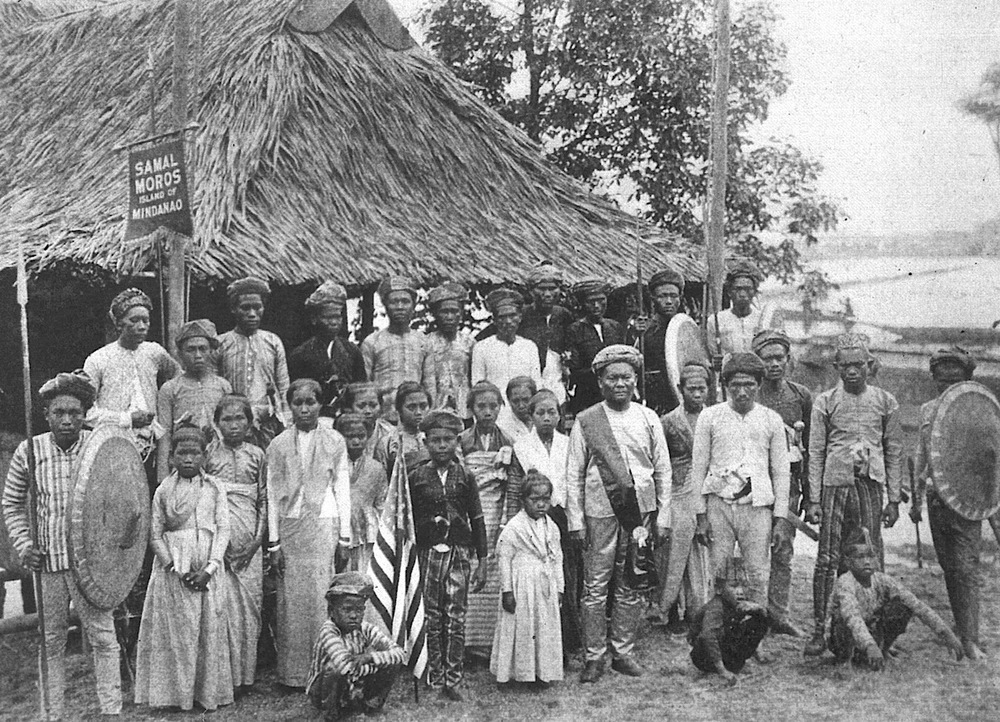

Moreover, there is an uncomfortable parallel between the plant species brought back and displayed for local people to visit and the way living human people were brought back to colonizer countries and placed in “human zoos” to entertain locals and push the ideology of superiority. The striking contradiction is that these “human specimens” were “displayed” to construct a vision of these ethnicities as “savages,” reinforcing racist ideologies that western societies have yet to fully dismantle (Baratay & Hardouin-Fugier, 2002); (Blanchard & Couttenier, 2017). These productions are built on the mission of “othering” the colonised people in order to maintain an emotional separation, never allowing the notion of fellow humans. The first known exhibit that would today be considered a “human zoo” was organized by Carl Hagenbeck in Hamburg in 1877, and the last major ethnographic display occurred at the 1958 Brussels World’s Fair, where Congolese people were exhibited in a recreated village setting (Baratay & Hardouin-Fugier, 2002); (Blanchard & Couttenier, 2017).

While botanical gardens play a role in showcasing foreign plant species, it is important to recognize the potential ecological harm these species can pose to native environments (Schneckenburger, 2010). Equally significant is the problematic legacy of displaying “exotic” plants, which often reinforces cultural stereotypes rooted in colonial narratives (Nielsen, 2023). What does it mean, then, when plants from colonized countries are deliberately labeled as “invasive”? What narrative does this framing support, and why is it being presented to the public in this way? Behind the grandeur of these displays lies a persistent bias that subtly upholds structures of cultural hierarchy, with ecological and social consequences.

So how can botanical garden curation restructure themselves to allow mitigation of ecological damage and remain mindful of cultural insensitivity? Perhaps it starts with approaching each individual species with curiosity and objectivity, instead of reproach and fear at the slightest unanticipated developments.

Botanical gardens and museums around the world have begun decolonizing their collections by reinterpreting displays and acknowledging colonial histories (Nielsen, 2023). But meaningful change goes beyond acknowledgement—it requires ongoing reflection, collaboration with affected communities, and a shift away from presenting Western knowledge as the only authority.

TIMELINE

A brief comparative timeline of colonialism, botanical gardens, human zoos

15th–17th Centuries: Start of European Colonialism

- 1492: Christopher Columbus’s voyage began the sustained European colonization of the Americas.

- 1600s: European empires (Spain, Portugal, Britain, France, the Netherlands) began large-scale colonial expansion and trade networks. This initiated the "Columbian Exchange"—a global transfer of plants, animals, and diseases (Kisling, 1998).

17th–18th Centuries: Early Botanical Gardens

- 1635: The Jardin des Plantes in Paris was founded as a royal medicinal herb garden (Nielsen, 2023).

- 1735: Pamplemousses Garden began in Mauritius as a private spice garden, evolving into a formal botanic garden under Pierre Poivre around 1767 (Schneckenburger, 2010).

- 1765: The Saint Vincent Botanical Garden in the Caribbean was established to support British imperial agriculture (Baber, 2016).

19th Century: Spread of Botanical Gardens & Rise of Human Zoos

- Botanical gardens grew in number across British and European colonies, acting as scientific and economic centers for the movement and study of crops like rubber, tea, and cinchona (Schneckenburger, 2010).

- 1877: Carl Hagenbeck established the first modern “human zoo” in Hamburg, showcasing people from Samoa and Africa in staged settings (Baratay & Hardouin-Fugier, 2002).

Late 19th–Early 20th Centuries: Peak of Human Zoos

- 1889: The Paris Exposition Universelle featured a "Negro Village" that drew millions and reinforced colonialist narratives (Baratay & Hardouin-Fugier, 2002).

- 1897: At the Brussels exhibition, 60 Congolese were displayed in a simulated village in Tervuren; at least seven died due to harsh conditions.

- 1904: The St. Louis World’s Fair included a "Philippine Exposition" with over 1,000 Filipinos displayed in ethnographic villages (Baratay & Hardouin-Fugier, 2002).

Mid–Late 20th Century: End of Human Zoos, Rise of Decolonization

- 1958: The Brussels World’s Fair featured a “Congo Village” where Congolese participants were displayed; this was one of the last known human zoos and faced global backlash (Baratay & Hardouin-Fugier, 2002).

- 1960s–1980s: Many African, Asian, and Caribbean colonies gained independence. This led to widespread criticism and reevaluation of colonial-era institutions, including botanical gardens (Nielsen, 2023).

ARTWORK

IMAGES

Part II. The Myth of Invasive Species

The Rhetoric of Botanical Otherness

Narratives are inherently subjective. They are influenced by the narrator’s biases, emerging from ingrained cultural norms, personal biases, and the context in which the narrative is presented.

In environmental science, terms including “invasive,” “alien,” and “aggressive” are commonly used to describe non-native species, which are often relocated by humans (Richardson et al., 2000). While these labels serve as ecological classifications, they also carry connotations that shape public perception of species, ecosystems, and even people (Hall et al., 2017). This language can and will subtly influence cultural and political attitudes, and is also a reflection of internal biases from individuals who establish this industry-standard language (Mattingly et al., 2020).

The xenophobic undertones of such terms frame “foreign” as inherently “threatening,” echoing colonial and racial narratives, which have been left unchecked for much too long (Vogelaar, 2021). Consequently and unsurprisingly, conservation discourse often includes harsh, militaristic language (including: “eradicate,” “eliminate,” “control”), which reflects more than ecological intent (Mattingly et al., 2020). Although narratives are subjective, they remain powerful tools for shaping ideology and public consensus.

It is particularly strange to use labels such as “invasive” considering that these plants did not migrate by natural or “independent” means such as water or wind, nor were they brought by foreign entities or individuals that may have had any hostile intent thus granting them the “invasive” label by proxy. No; they were brought into the colonizer countries by their own people willingly and eagerly, as trophies from travels (Hall et al., 2017). Upon deeper reflection, being so far and abruptly displaced from home, these plant species more often empathically reflect a refugee status in a foreign land.

In their new environments, these species face ecological dislocation and must adapt simply to survive. Many require special care, which reinforces a relationship of dependency between plant and human caretaker which is the expected and comforting notion while bringing them to new land. However, if and when these plants survive without assistance, sometimes outcompeting local species, they are quickly labelled as dangerous (Richardson et al., 2000). This narrative looks past the difficult reality of these displaced organisms, seeking to coexist but snowballing into dominance by environmental conditions and the absence of balancing ecological relationships.

There is a drastic difference in how we describe species: a native plant spreading into new territory may be called “spreading” or “aggressive,” and though the latter does have a negative connotation, it is not as alienating and ironically pointed toward deliberate cultural othering that non-native plant species receive (Vogelaar, 2021).

If we also consider the fact that many non-native or disruptive plants thrive in disturbed soils, we also face the responsibility that these conditions are often created by human activity. Before large-scale agriculture and urban development, such disturbance was minimal, occurring through natural events like landslides or animal movement (Hobbs & Huenneke, 1992). But today, deep soil networks and self-sustaining ecosystems are frequently disrupted, creating opportunities for rapid plant spread regardless of origin (Ellis et al., 2010).

Case Study: Himalayan Balsam

A particular plant species identified as a widespread invasive plant in England and Wales is the Himalayan balsam, scientifically named Impatiens glandulifera. It is recognised as ecologically disruptive due to its impact on riverbanks during its peak growth period and then dying back completely afterwards, leading to unprotected soil, thus contributing to erosion, altering sedimentation patterns, and causing long-term effects on local ecosystems and, potentially, broader landscapes (Tickner et al., 2001). For these reasons, the species requires careful monitoring and considered management.

Introduced to the United Kingdom through Kew Gardens in 1839 as an ornamental and honey-producing garden plant, Impatiens glandulifera “escaped” and established itself in the wild (Beerling & Perrins, 1993). Its success as a widespread development is attributable to several competitive traits. The plant produces abundant nectar and has a distinctive floral scent, making it highly attractive to pollinators (Lopezaraiza-Mikel et al., 2007). It is sometimes referred to as a “poor man’s orchid,” which seems like a backhanded compliment as we explore the nature of this plant.

Beyond its ecological behaviour, the species has been involved with traditional and homeopathic medicinal uses as well. Ethnobotanical records indicate the flowers have cooling properties, the leaves can be applied to burns, seeds may be used as a diuretic, and root juice has been traditionally used to treat hematuria (blood in the urine) (Duke, 2002). In certain traditional medical contexts, it has also been used to alleviate joint pain, depression, and some nervous system disorders. Phytochemical analyses report the presence of compounds with antioxidant, antimicrobial, anti-proliferative, and anti-cancer activity. In homeopathy, Impatiens glandulifera is included in Bach Flower Remedy No. 18 (Impatiens), intended to promote patience, empathy, and gentleness, and is a component of the Bach Rescue Remedy, marketed for use during acute stress, emotional strain, or shock (Bach Centre, n.d.).

The plant’s reproductive strategy further supports its dominance. It produces large quantities of seeds contained in explosive pods capable of projecting seeds several metres. This ballistic dispersal, combined with downstream transport by rivers and streams, facilitates rapid colonisation of suitable habitats (Beerling & Perrins, 1993).

Although the plant is often identified for swift eradication, a gentle intervention strategy seems mutually enriching. Establishing clear thresholds for acceptable population levels can help maintain “soft boundaries,” allowing the species to persist without overwhelming native flora. Low-tech methods will avoid the ecological risks associated with chemical herbicides, which may impair soil health and have long-term detrimental effects on both ecosystems and human health when used in proximity to inhabited areas (Pretty, 2008).

While there are options of physical and chemical controls (including soil texture and pH calibrations), the most sustainable and respectful management may involve creating a supportive plant community that limits the competitive dominance of Impatiens glandulifera. Co-planting native species with similar soil preferences and non-competitive species naturally occurring alongside Himalayan balsam in its native range could form a self-contained, balanced ecosystem (Hulme, 2006). In such contexts, the plant could be confined to defined habitats—perhaps integrated into designed landscapes such as ponds bordered by diverse vegetation—where its ecological impact is controlled, and its aesthetic, scientific and cultural values can be appreciated.

The narrative framing of the Himalayan Balsam as a nuisance and problem reflects the colonial view that continues to shape perceptions of South Asian immigrants in England. Both are labelled outsiders, reinforcing hierarchies of belonging. Such narratives erase the deep histories of exchange, labour, and cultural contribution that have already woven them into the fabric of the “host” nation. Just as eradication of the Balsam overlooks its ecological and medicinal value, exclusionary behaviour toward immigrants dismisses the enrichment that comes from cultural diversity. Reframing these stories requires dismantling colonial logics, seeing both plants and people as additive, celebratory and now embedded and integral to our evolving landscape (Vogelaar, 2021).

ARTWORK

IMAGES

%201.png)