Before diving into the fascinating story of lacemaking in India, it is important to understand the politics of the fabric itself. Lace, a gauzy and highly ornamental fabric, is made using a variety of interlooping techniques. The only requirement? Yarn, a few basic tools and a skilled lacemaker. Lace was a novelty among aristocratic and affluent classes in Europe and European colonies in the 15th–20th centuries, and the global demand for it grew exponentially as markets gradually opened up to the rest of the world.

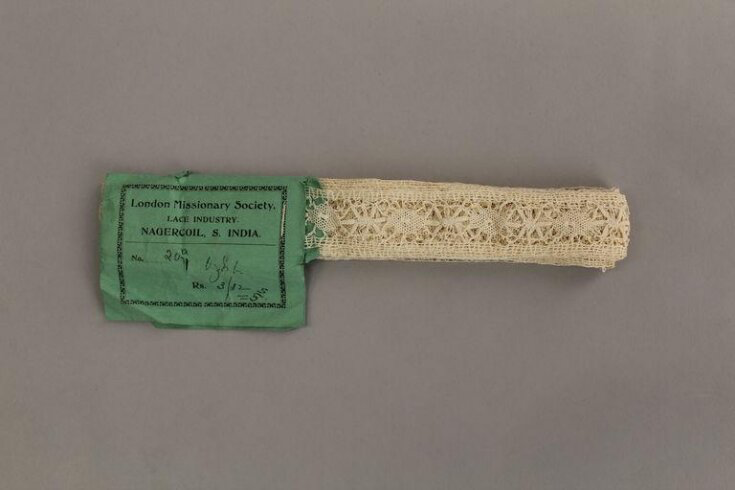

One might associate lace with lingerie or exclusively feminine clothing today. However, this gendered perception is a recent development in its vast history. Both men and women used to proudly wear lace-adorned clothing in the past, and decorate their houses with it (img. 2), however, the lacemakers historically and to this day, are women—and this luxurious fabric comes at a cost.

Lace cannot be made in a hurry. The delicate fabric is time consuming and expensive to produce.

The sheer economic opportunity in this industry resulted in women across Europe, most notably in Italy, in the 18th–19th centuries both voluntarily gravitating towards the craft and being coerced into learning it, especially in churches where the nuns would make lace tirelessly. When these nuns arrived in India, they brought the craft along with them. And the men—both the missionaries and locals—created an industry out of women’s labour.

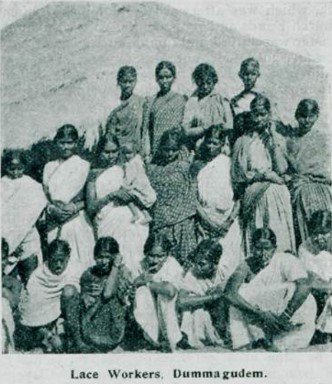

Lacemaking flourished in port towns along coastal Andhra Pradesh and Kerala, such as Narsapuram, Dummugudem, Eravipuram and Kanyakumari and even some Goan villages. The introduction of lacemaking in India is attributed to Portuguese missionaries in the 19th century, much after the original voyages post the discovery of India by Vasco De Gama in the 15th century. There are some accounts of lacemaking going back to the 16th century in Kerala. However, it was established as a profitable business only later, especially among Dalits who converted to Christianity, providing them economic opportunities by selling the lace they made overseas. It was a means to overcome the social boycott they faced, and to earn a livelihood during famines. This coincided with the lace boom in the world in the 18th–20th centuries. (img 3)

Convert women from the Mala and Madiga communities in Narsapuram were among the first to learn this craft. It allowed them to become ‘housewives’ by discontinuing working as agricultural labour, thus, elevating their status in Indian society at the time. Upper caste Hindu women did not step out of their homes to work, which was seen as a sign of wealth and social power. These ideas were also reinforced by the Christian missionaries. By renouncing work in the fields, a sense of equality, hitherto impossible, was achieved.

Opportunist women belonging to upper castes were also drawn to the craft, such as Kapu women, followed by men from other dominant castes such as Banias, bringing lacemaking outside the direct control of Christian missionaries. Dutch and British missionaries in India also encouraged and supported the craft, taking it to different regions in the country such as Punjab and Calcutta, leading to its widespread adoption. Narsapuram, however, continued to be the biggest exporter (img. 4).

The lacemaking industry in Narsapuram grew considerably in the early 20th century, experiencing a decline only after 1953 due to trade sanctions, increasing internal competition and the introduction of machine-made lace in the market. It grew again in the 1970s as new markets were explored, especially in the middle-east.

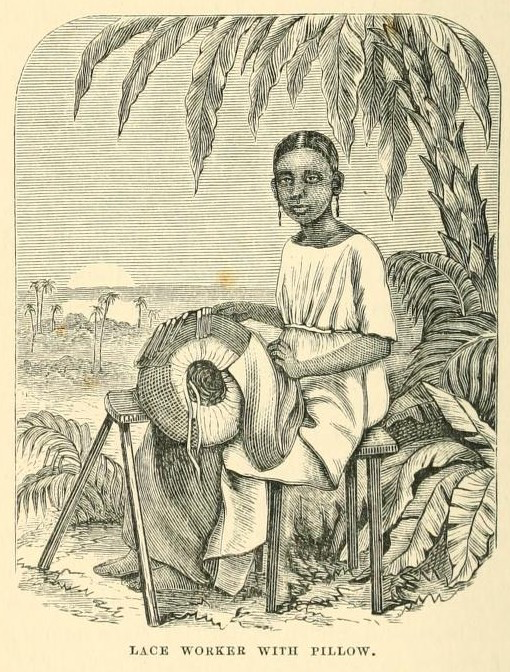

Lacemaking in India can be broadly divided by technique—Crocheting, involving the use of a single needle and thread employing interlooping as the main technique, and Bobbin lace involving the use of multiple bobbins and complex interlacing techniques. While crocheting requires just a curved hook for the textile to be produced, bobbin lace involves paraphernalia such as pillows and multiple smaller needles holding the delicate fabric in place. Other techniques such as tatting are also popular, but not at an industrial scale.

Changing patronage over time might explain the preference for different lacemaking techniques in different places, such as crochet in Narsapuram and Goa, and bobbin lace in Kerala. This preference may also depend on ease of production upon the monetisation of the craft. Crocheting takes considerably less time than bobbin lace, which might have led to the massive success of Narsapuram as a lace trading hub in the

20th century. While exports suffer today due to changing tastes and trends, Narsapuram still supplies lace to the rest of India (img. 5).

Just as in Europe, lacemaking was not always taken up voluntarily by women. In Goa, there are accounts of the craft being forced upon the locals until it was eventually adopted and made an indispensable part of Goan culture. It was not always an act of benevolence, as opposed to a quest to ‘civilise’ the locals, with Christian values of propriety being imposed, redefining what womanhood meant (img. 6). While the intentions

of the missionaries may often have been questionable, it is undeniable that many practitioners saw it as a way to escape the everyday cruelties of caste-based discrimination by finding dignity in work (img. 6).

As with any craft and craft based industry, the future of lacemaking is uncertain. Being women’s craft, often unpaid or severely underpaid and for domestic or religious use, lacemaking is currently on the verge of disappearing, especially from places where it was historically produced and part of the local culture (img. 7).

While the technique of bobbin lace remains scarce, crochet is fast becoming a hobby for many and is no longer a craft just for women. However, this is due to vastly different socio-cultural reasons that have little to do with the history of lace in India. The most crucial factors aiding in its widespread adoption are the simple equipment required, access to tutorials and the ease of learning. In the larger context of ensuring the longevity of crafts, lacemaking can be seen as one in which specific techniques are being lost while others become increasingly popular, simultaneously. It says something about the cyclical nature of craft, of reinvention, and of knowledge sharing. In specifically the Indian context, it poses as an example of a craft transcending community-based occupation as is typically seen. It does, however, raise questions about what it means for a craft to be traditional, who owns it and is allowed to practice it, and who eventually benefits from it.

%201.png)