Sana's training in miniature painting has deeply influenced her artistic path, leading her toward a contemplative and spiritual approach. The meticulous, repetitive technique sparked her interest in spiritual philosophies, particularly Sufism, shaped by her family's lineage of saints in India. Through her practice, she explores the meditative aspects of art-making, believing in its transformative power to access higher consciousness. For Sana, creating art is a form of prayer—a source of healing, wholeness, and a way to cultivate divine energies within and around us.

1. Tell us about your background—what first drew you to art, and how did your journey as a creative begin?

My father is a painter in Pakistan, and when I was younger, he was a great inspiration for me. We come from a humble background, so we genuinely did follow the cinematic art school dream, which was entirely unique where we’re from. However, over time, he recognised the difficulties the creative arts pose and discouraged me from pursuing it. I couldn’t imagine myself doing anything else; I chose my path in defiance of my parents' wishes, and my friends came together to pull in the admission fee. I went on to pass the interviews and tests for the National College of Arts, Lahore, the oldest and most prestigious art school in Pakistan. I never imagined it would eventually become my path, but I welcomed the challenge of it.

My creative journey really deepened after I became a mother and started processing the loss of my own mother. That dual experience of nurturing life while grieving another forced me to search for meaning in new ways.

Art became a form of healing, but also of connection. It wasn’t about the “art world” or galleries—it was about staying present with myself. About honouring grief and joy as two sides of the same feeling. I often say I didn’t choose art—it chose me. It emerged as a spiritual practice, as a way to sit with pain, love, and everything in between.

2. You’ve mentioned that your identity as a mother plays a significant role in your work. How has that influenced or evolved your practice over time

Becoming a mother while losing my own mother was a really difficult time—I didn’t know how to be a mother, and she wasn’t there to guide me. After a few years, I felt this pull back to my practice, like I was here for a purpose beyond just my physical responsibilities. When I returned to painting, my first work was a polar bear holding a bear cub, inspired by a documentary on climate change that made me deeply worried for my daughter’s future. I realised that motherhood isn’t just about caring for one child—it’s about feeling connected to Mother Earth, to all mothers, to the world itself. It widened my lens, made me more aware of things like sustainability and the small ways I could make a difference, even if it’s just putting up a poster to educate one person.

Motherhood has been transformative—for my life and my art. It’s made me more intuitive, more attuned to emotion and energy. When I see a child cry, I feel it in my bones. That kind of empathy has changed how I make work.

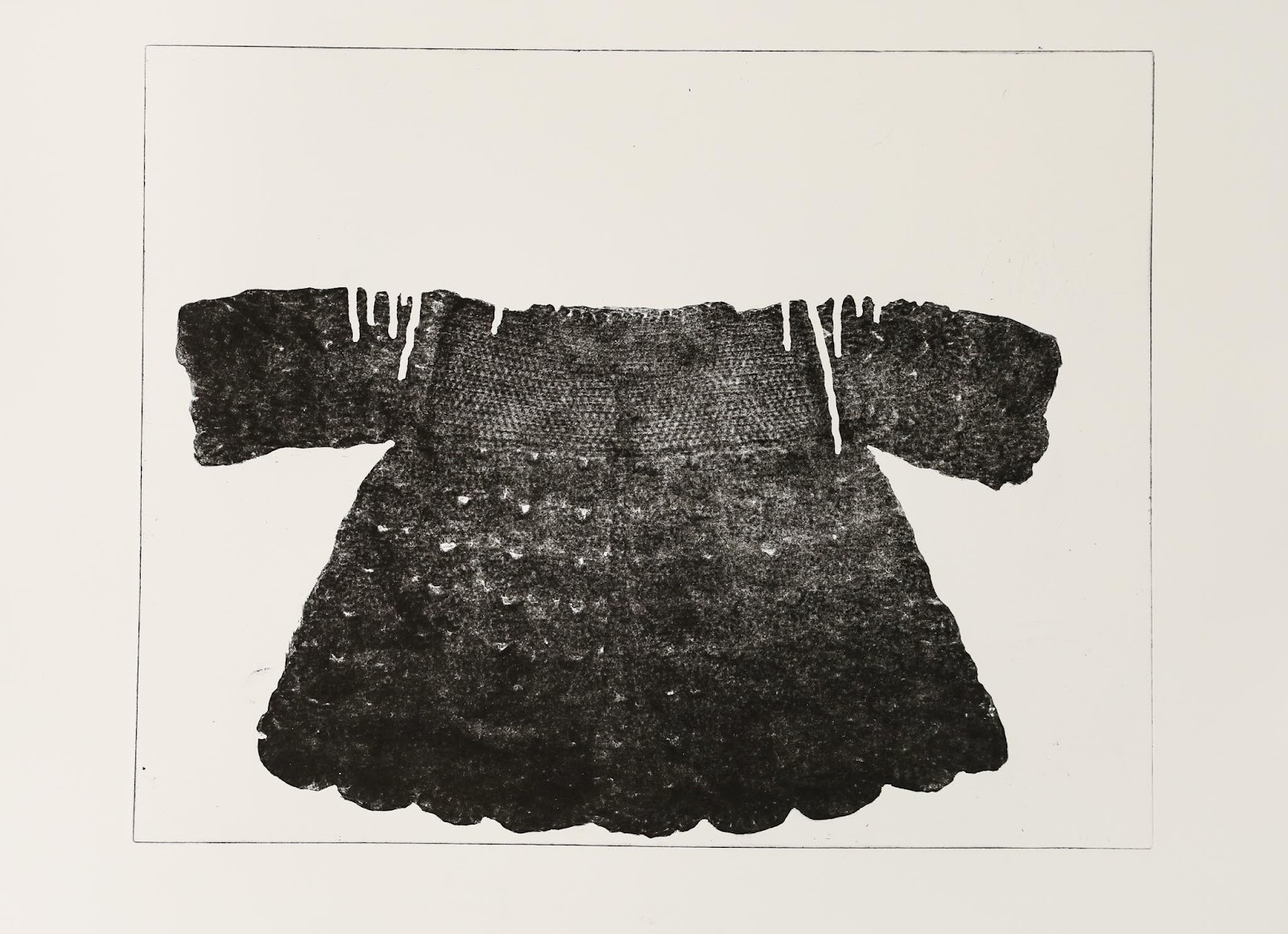

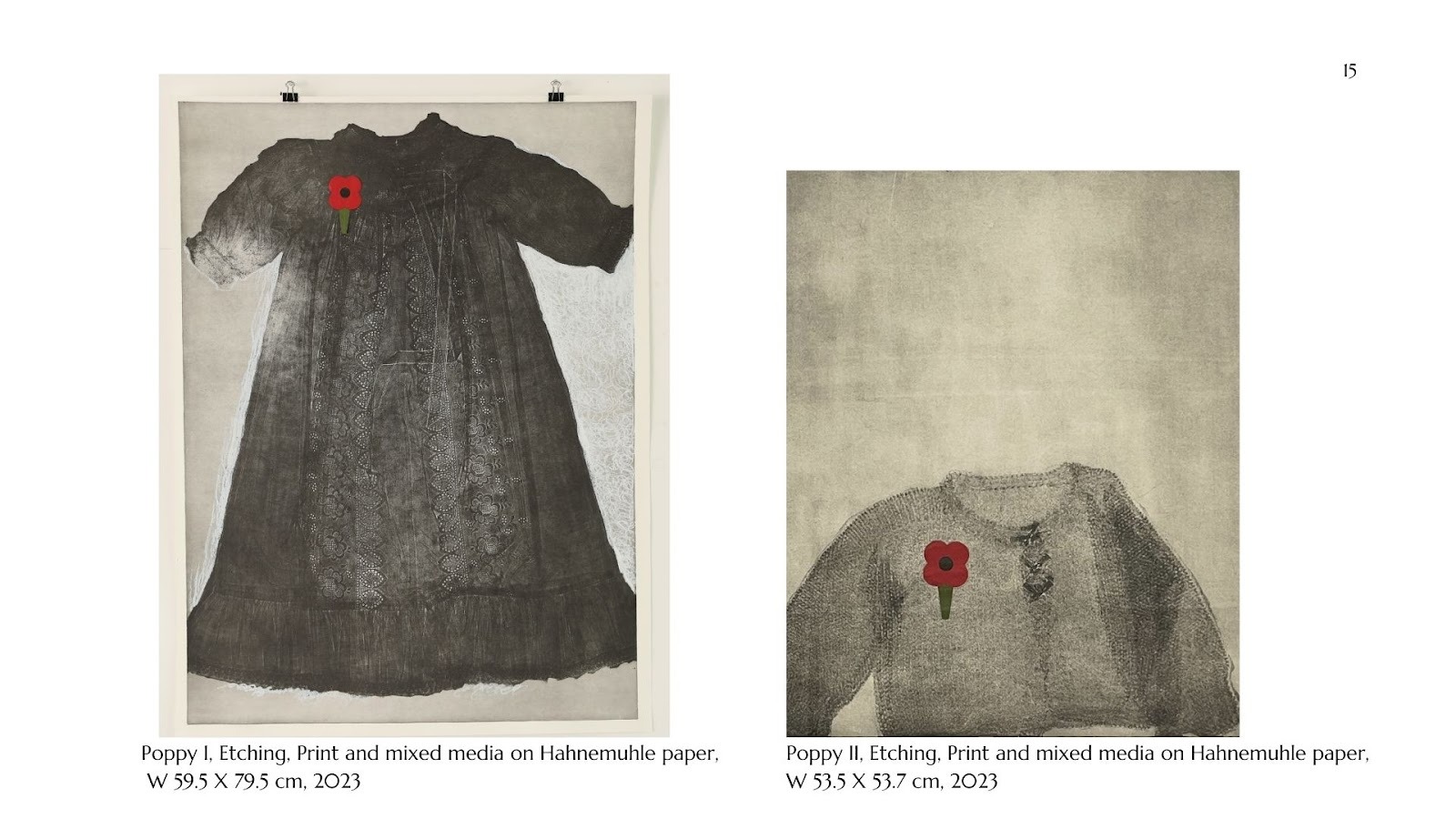

For instance, I created a series of fragile sculptures, born out of my deep emotional response to the vulnerability of children in war zones. inspired by this sense of vulnerability. They were placed at the centre of a space—delicate, breakable, partially buried in sand. People had to walk around them carefully. These pieces were shaped by my grief and horror at witnessing the suffering and loss of innocent lives.It was a way to say: We are fragile. We need care. Some sculptures were already broken. Some were still standing. I wanted the work to speak to that pain, to acknowledge it and hold space for it so that it is not forgotten.

In that vein, motherhood to me is a state of being, a powerful, energetic space driven by love and the instinct to protect what is vulnerable. It is a force that draws strength from tenderness, and the will to heal, shield and nurture despite the fragility of life.

All of this,That, to me, is motherhood—carrying loss and love at the same time.

“So much pain comes from love. When you feel it that deeply, it becomes the source of your art.”

3. Your work engages with themes of loss, war, and maternal grief. How do you approach translating and processing such profound emotions into visual art? How do you stay motivated?

Art is my way of expressing emotions I can’t vocalise; my work emerges naturally from experiences that deeply move me. I don’t use any particular medium; I’m the medium, and I let the work come to me. Sometimes, if something strikes me, the work just flows out. Processing grief and war, especially as a mother, is overwhelming; But when I return to my studio, I let my emotions guide me, using physical gestures, prayer, and recitation to translate pain into visual form.

It’s not a calculated process—it’s a felt one. My work comes from deep meditation and prayer, from tuning into the present moment. If I’m aware of what I’m feeling, and I create from that awareness, then the work carries that feeling. You feel it because I’ve felt it.

Staying motivated isn’t always easy, but I don’t force it. I follow intuition. Some days, I make prints. Some days, I cook. Some days, I simply sit with my daughter and listen. I don’t believe in separating life and art. They are one.

4. Your recent work, influenced by the genocide in Gaza, is both powerful and heartbreaking. Can you tell us about how this project developed and what you hope your audience can take away from it?

This work emerged from grief and helplessness. I was overwhelmed watching what was happening in Gaza. I couldn’t look away. I didn’t want to.

So I started creating from that place—from rage, from heartbreak, from love. The sculptures, the performances, the tea gatherings—they all came from this need to hold space for sorrow, and also to honour the sacredness of life. It emerged from a prayer for their souls to rest in peace, and a way for me to sink my body movement into my recitation. I wanted myself and the audience to slow down and feel what’s happening.

I want them to remember that we are all connected. That behind every number, every statistic, there is a child, a mother, a community shattered by loss.

“I want people to feel the love through pain—because they go together.”

5. How has your own arts education evolved your practice? Now that you’ve completed your MFA at GSA, how do you reflect on that experience?

Coming into the MFA after a seven-year gap—during which I became a mother and processed deep personal grief—I was ready. I was motivated, searching for my people, my tribe. But I quickly realised how divided things were. I felt isolated in the cohort. There was a sense that I didn’t fit in—because I was married, a mother, and older. No one asked me to go out, no one included me in the social spaces.

I realised that inclusion in the art world often isn’t automatic, especially for people like me. But my tutors were incredibly supportive. I threw myself into my work.

One of the most important things I did was my research project, called Third Space, which explored how artists from different cultural backgrounds can share space with care and intention. It made me realise that even when we occupy the same room, we don’t always meet. True connection takes effort. It takes balance.

6. What are your aspirations for the South Asian creative community in the future? Do you have any advice for emerging artists (and mothers!) navigating similar spaces?

Wherever we are, we can feel at home if we’re truly connected to ourselves. It’s good to evolve, to embrace freedom, but we also need to remember where we come from. It’s easy to reject parts of our culture or tradition, but those things shape us in ways we can’t erase. If we embrace every part of ourselves—our roots, our experiences—we become whole, unique, and truly authentic.

“Be grounded. Be authentic. If you embrace all of yourself, you’ll find confidence you didn’t know you had.”

7. What projects are you currently working on, and where can we expect to see your work in the coming months?

I’m very excited about what’s coming up. I’m currently going to a residency called Women in Print at the University of Central Lancashire. It’s an opportunity to explore new directions in printmaking and video.

Then in April, I’ll be part of Magnetic North, a residency that focuses on balance and spiritual practice. For that, I’ll be continuing my Tea Party project—creating sacred spaces of gathering, food, and conversation.

In May, I’ll be in Nuremberg, Germany, for Blue Night, a live performance event held in the ruins of Saint Catherine’s Church. I’ll be creating a wall-based installation there. Each of these projects allows me to work in different forms—print, food, ritual—and that’s how I like it. My work lives in many mediums, but the intention stays the same.

8. And finally, what is your favourite South Asian sweet?

Oh, I love all kinds of sweets! But my absolute favourite is koya kulfi—the kind they used to sell from carts back in my village in Pakistan. The seller had a red matka (earthen pot) filled with ice, and he’d pop open the metal lids of the kulfis with a knife. It was simple, cheap, and absolutely delicious. I haven’t found anything like it here in the UK.

%201.png)